Didactic literature, from the Greek didaktikos, or skillful in teaching, refers to literature that overtly demonstrates a truth or offers a lesson to readers. Not a subtle approach, didacticism delivers a specific and pointed message and was present in the earliest stories developed to teach moral behavior, such as fables and parables.

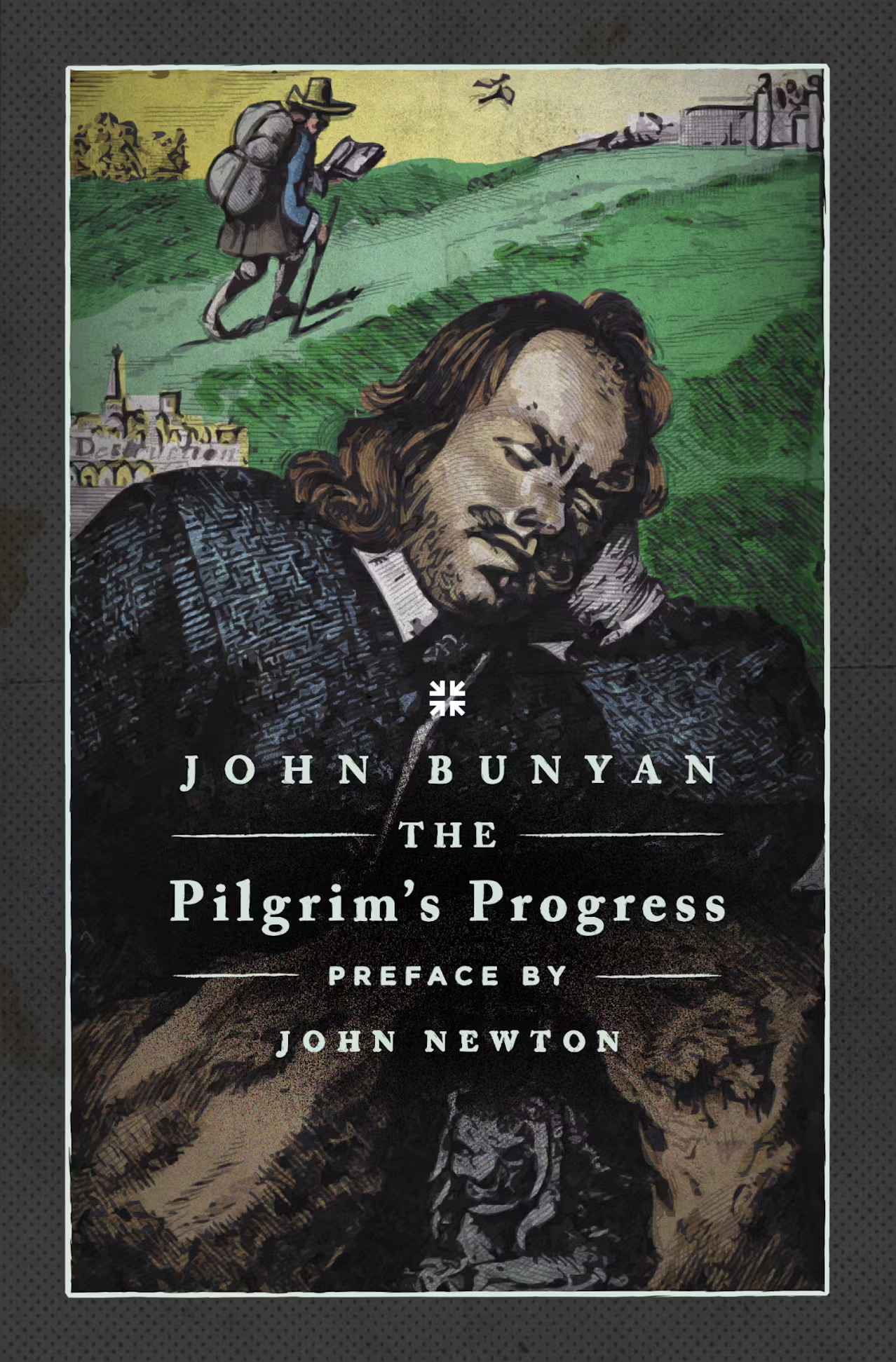

Medieval allegory proved didactic in its forceful presentation of commentary on religious and ethical doctrine and became refined in Renaissance works such as Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590 and 1596), a commentary on social conditions in 16th-century England, and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678 and 1684), in which an allegorical character named Everyman searched for spiritual fulfillment. Authors also might insert themselves into their own novels in a method termed authorial intervention, interrupting their narrative to speak directly to the reader for instructional purposes.

Didacticism remained long entrenched in stories for children, particularly with the rise of Puritanism and attempts to reform the Church of England from the 16th through the 17th centuries. Until the 18th century, all children’s literature served to instruct. Following the French Revolution (1789–99), egalitarian principles spread to England, and children’s literature grew less preachy, although writers still strove to teach a lesson.

The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) theorized that children were not merely small adults but thinking beings whose mental and emotional needs should be considered separate and apart from those of adults. Through the end of the 18th century, English children’s literature tended to feature all-knowing adult characters, which often interrupted action to deliver sermons to readers. Maria Edgeworth followed this format in her two story collections for children, The Parent’s Assistant (1796) and Moral Tales (1801). Decades would pass before literature devoid of didacticism, such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1872), offered children entertainment, and children’s literature could be read for its own sake.

Thesis novels offered strongly didactic messages to adults during the first half of the 19th century. Authors whose fiction overtly highlighted the disgrace of depressed social and economic conditions for the working classes and emphasized the inequities of class structure included Charles Dickens, Frances Trollope, Benjamin Disraeli, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Charles Gissing. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s novel-poem Aurora Leigh (1856) features didacticism in her defense of the intellectual and creative rights of women.

By the 20th century, a more sophisticated reading audience demanded more subtlety in its fiction. Authorial intervention proved unacceptable, and didacticism became a narrative technique of the past.

Bibliography

Demers, Patricia, and Gordon Moyles, ed. From Instruction to Delight: An Anthology of Children’s Literature to 1850. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Morse, David. The Age of Virtue: British Culture from the Restoration to Romanticism. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Categories: British Literature, Literary Terms and Techniques, Literature, Novel Analysis

Edwardian Era

Edwardian Era  Bildungsroman

Bildungsroman  The Yellow Book

The Yellow Book  Oxford Movement

Oxford Movement

You must be logged in to post a comment.