Critic M. L. Rosenthal coined the term “confessional poetry” in his review of Robert Lowell’s Life Studies (1959) in the 19 September 1959 issue of The Nation, noting that while most poets conceal themselves, “Lowell removes the mask.” The term came to identify the intensely personal style wherein the “I” is essential to the inception, construction, and resonance of a poem. Subsequently, John Berryman, Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roethke, Anne Sexton, and W. D. Snodgrass were also categorized under this heading, arousing debate among critics ever since.

Some argue that writers are only human and, as such, are incapable of being completely forthright, as the term suggests. Others contend that all poetry is confessional to a degree, often pointing to the sonnets of Petrarch and William Shakespeare as the first confessional poems. In the end, though, the argument should settle on one fact: the confessionalists were the first to write with such candor about what might be perceived, in Rosenthal’s words, as “rather shameful” personal subjects; this characteristic alone became their trademark.

To best understand the confessional movement, one must first be aware of the historical and cultural context that gave rise to it. America had just suffered through its second world war. The devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, coupled with the Cold War and the imminence of a nuclear attack, made the complete annihilation of mankind a conceivable notion that sank deep into communal consciousness.

What resulted was best explained by the critic Walter Blair with a passage from John Steinbeck’s The Winter of Our Discontent (1961): “When a condition or a problem becomes too great . . . it goes inward and . . . what comes out is . . . a compulsion to get something—anything—before it is all gone. Maybe the assembly-line psychoanalysts aren’t dealing with complexes at all but with those warheads that may one day be mushroom clouds.” So it stands to reason that, in the atomic age, poets would turn their focus inward to the atomic machinery of human emotion.

In the postwar years America as a whole was straining with growth. Deurbanization breathed life into the suburbs, and a renewed sense of conformity for some meant alienation to others, thereby begging contemplation for the mindful poet. Racial tensions were escalating, as were calls for equality. The confessional poets, however, did not address these issues as directly as their more socially conscious contemporaries.

Instead, they turned inward to explore the “self” as it related to familial roles, commonly held beliefs, and the cultural norms of the day. This is not to say they cowered from the uncertainty of their times. To the contrary, they internalized their uncertainty only to re-envision the endemic alienation and procedural dehumanization in their writing, believing that the commonality of human privacy was their last, best hope. This was an age when all hope for salvation seemed to have vanished from public life. So confessional poets excavated their souls in hopes of finding something infinite in the finite.

As Mark Doty explains in his essay “The ‘Forbidden Planet’ of Character: The Revolutions of the 1950s,” the confessional poets emerged on the literary scene not by opening the window but by breaking it down. Compared to the dogma of their Modernist predecessors, who aimed to write impersonal poetry, the confessional poets’ more-candid style was revolutionary.

In many ways, the confessionalists were the Modernists’ natural heirs, due in no small part to their similar themes. Alienation is one of the more obvious thematic parallels. Take, for example, the utter hopelessness in the conclusion to Lowell’s “Walking in the Blue” (1946): “We are all old-timers / each of us holds a locked razor.” Another theme shared with the Modernists—and more specifically, T. S. Eliot—was the depiction of the world as a vast wasteland. In Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922), the hallmark of Modernist poetry, he describes the world as a disjointed collection of random pieces that may or may not amount to a whole.

The Modernists believed that only hollow men could people such a world. Yet another sensibility shared in Plath’s poem “The Thin People” (1957): “They are always with us, the thin people / Meager of dimension as the gray people.”

Although the confessionalists’ penchant for lavishing their verses in exquisite language was also consistent with Modernist practices, it is in their technique that they differed most. Unlike their forbears, the confessional poets frequently offset their dense poetic language with autobiographical insight written in such a frank, colloquial tone that it felt like a confession between friends.

A good example of this tendency is seen in Lowell’s “Skunk Hour” (1959), in which the poet writes, “Lights turned down, / they lay together, hull to hull, / where the graveyard shelves on the town.” He then stops in mid thought and admits, “My mind’s not right.” Sexton displays a similarly typical candor in “The Black Art” (1962): “A woman who writes feels too much . . . / She thinks she can warn the stars. / A writer is essentially a spy. / Dear love, I am that girl.”

Another divergence was marked by the prominence of metaphor and personification rather than reliance on the solitary image or allusion that often characterized Modernist poetry. Whereas Ezra Pound describes the world in his “Canto XXX” (1948) with an obscure allusion to papal corruption, Plath uses the metaphor of an axle that “grinds round, bearing down” in her poem “Heavy Women” (1962).

Where Modernist William Carlos Williams’s “Death the Barber” (1922) makes a haircut an image of death, a spider “marching through the air” turns into a metaphor as Lowell’s poem “Mr. Edwards and the Spider” (1946) concludes with the lines, “To die and know it. This is the Black Widow, death.” “Little houses” become a metaphor for secrets in Sexton’s “Barefoot” (1969), just as John Berryman’s “Dream Song 29” (1964) depicts a recurring thought as “the little cough somewhere, an odour, a chime.”

Personification also dominates confessional poetry, mainly as an attempt to restore something missing to the world. For instance, by keeping the attributes of the moon and the woman ambiguous in “Barren Woman” (1961)—“The moon lays a hand on my forehead, / Blank-faced and mum as a nurse”—Plath allows nature to personify the woman and vice versa. Personification functions similarly in most confessional poetry. By making the poet’s soul a surrogate for nature, humanity and the world are reconnected, one becoming an intrinsic part of the other.

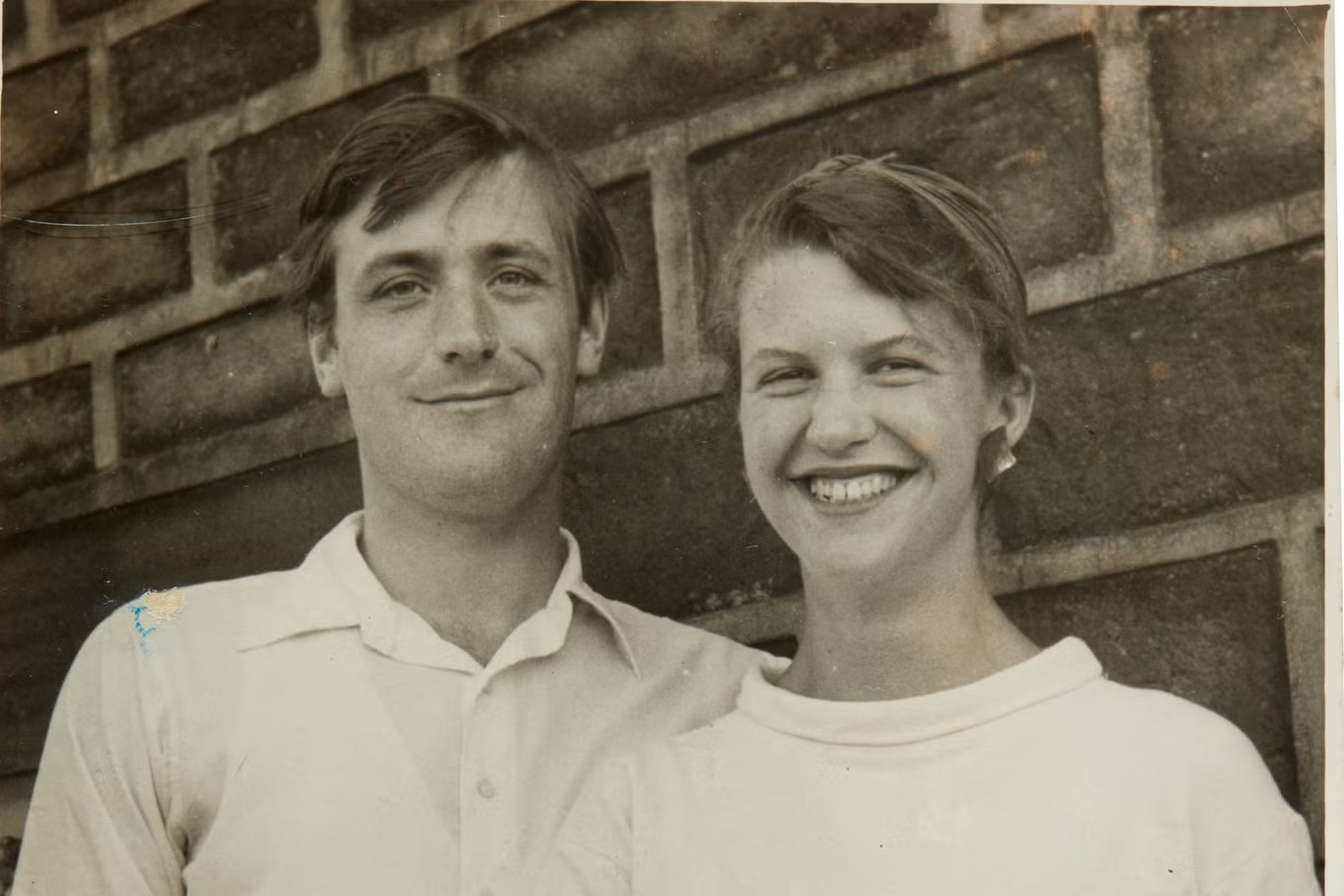

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath

Confessional poetry also introduced new personal subject matter, which challenged the New Critical approach, popular in the 1950s, that focused sharply on the work rather than the author. The confessional poets created poetry from everyday occurrences; from the monotony of routine they drew enlightenment. Plath’s poem “Mirror” (1961) could stand as their credo: “I am silver and exact . . . / Whatever I see I swallow immediately / Just as it is, unmisted by love or dislike. / I am not cruel, only truthful.”

Plath called this the poetry of “real situations, behind which the great gods play the drama of blood, lust and death.” Critics Kate Sontag and Donald Graham reiterate this idea: “First-person lyrics can embrace a larger social vision, achieving . . . universal resonance.” For example, Sexton’s “The Fury of Sunsets” (1974) captures universal doubt in a few short personal questions: “Why am I here? / why do I live in this house? / who’s responsible?”

For any poem to render meaning, it must first coax its reader into becoming an accomplice, which confessional poetry achieves by relating to the reader, reducing the provocations of the larger society to a microcosm of everyday life. As such, Plath identifies not only the acceptable mores of motherhood but also those darker privations of being human. In “Words for a Nursery” (1957) she offsets a positive view of motherhood with one more sinister: “I learn, good circus / Dog that I am, how / To move, serve, steer food, / . . . My master’s fetcher.”

Similarly, Berryman uses the persona of Henry in his poem “Dream Song 1” (1964) to explore the role of men in the world: “All the world like a woolen lover / once did seem on Henry’s side. / . . . I don’t see how Henry, pried / open for all the world to see, survived.” Merely in the act of translating society’s expectations into their own words, Plath and Berryman regain control and are, in a sense, emancipated by their understanding.

Confessional poetry was also interested in the psychology of marriage, parenting, love, work, and faith. This is especially true of Sexton, who is famous for saying, “Poetry led me by the hand out of madness.” Notice her distinctively psychological overtures in “Despair” (1976): “Despair, / I don’t like you very well. / You don’t suit my clothes or my cigarettes. / Why do you locate here . . . ?” Lowell shows a similar inclination in “Waking in the Blue”: “Absence! My heart grows tense / as though a harpoon were sparring for the kill. / (This is the house for the ‘mentally ill.’)”

What Berryman is saying with his use of capitalization in “Dream Song 14” (1964) is no accident either: “And moreover, my mother told me as a boy / (repeatingly) ‘Ever to confess you’re bored / means you have no / Inner Resources.’ I conclude now I have no / inner resources, because I am heavy bored.”

Many critics have argued that this intensely psychological style is to blame for the steep decline in the popularity of poetry over the latter half of the century, overlooking the fact that any substantive explanation of this trend must include a variety of other factors as well. There is little doubt, however, that the confessional poets’ search for resolution in the latent power of the human psyche prompted movements such as Personalism, Language Poetry, and New Formalism.

Poets Sharon Olds, Denise Levertov, Adrienne Rich, and Audre Lorde (to name a few) owe them an equally profound debt because, in the end, confessional poetry’s groundbreaking techniques, themes, and subject matter ignited a revolution that changed the landscape of poetry in the second half of the twentieth century.

Topics for Discussion and Research

- Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in “The American Scholar”: “Let us be Americans . . . As the source of truth is not books, but mental activity, we are to cultivate self-trust . . . in ourselves we find the law of all nature.” With regard to this statement, is it wise to single out any specific group of American poets as “confessional”? Use specific examples from other movements in American poetry to defend your argument. See Yezzi’s article “Confessional Poetry & the Artifice of Honesty” in The New Criterion and Gregory’s article “Confessing the Body: Plath, Sexton, Berryman, Lowell, Ginsberg and the Gendered Poetics of the ‘Real’” in Modern Confessional Writing: New Critical Essays.

- Poets Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson were among the first American poets to explore the idea of the “self.” What common themes, techniques, and subject matter associated with confessional poets also appear in the poetry of Whitman and Dickinson? In what ways are the confessional poets distinct from these American predecessors?

- Confessional poetry was both a continuation of and a reaction to the Modernists’ impersonal poetry. Choose any anthologized Modernist poem and one of a confessional poet and analyze the literary devices used. In what specific ways does the confessional poem modify the approach to poetry illustrated by the Modernist poem?

- A common theme in the work of Plath and Sexton is the role of women as daughters, wives, and mothers. Take Plath’s poem “Daddy” and Sexton’s poem “All My Pretty Ones” and compare the poets’ attitudes toward their fathers and their own role as women in society. For insight into their work see Bundtzen’s Plath’s Incarnations: Woman and the Creative Process, as well as Hall’s chapter titled “Transformations: Fairy Tales Revisited” in Anne Sexton.

- Confessional poetry internalizes cultural issues rather than addresses them directly. Analyze either “To Speak of Woe That Is in Marriage” or “Man and Wife,” both written by Lowell, and explain how the poet approaches society’s views of gender indirectly, then compare Lowell’s approach to Berryman’s in “Dream Song 29.” For further insight into these two poets, see Cosgrave’s The Public Poetry of Robert Lowell, Williamson’s Pity the Monsters: The Political Vision of Robert Lowell, and Thomas’ Berryman’s Understanding: Reflections on the Poetry of John Berryman.

Resources

Criticism

Lynda K. Bundtzen, Plath’s Incarnations: Woman and the Creative Process (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983).

Critical essays with unusual perspectives on the feminine identity in Plath’s work.

Patrick Cosgrave, The Public Poetry of Robert Lowell (New York: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd., 1970).

Review of Lowell’s poetry that prompted him to dedicate a revised draft to Cosgrave.

Jo Gill, ed., Modern Confessional Writing: New Critical Essays (London: Routledge, 2005).

Multiple perspectives on the influence of the confessionalists on contemporary writers.

Caroline King Barnard Hall, Anne Sexton (Boston: Twayne, 1989).

An introduction to Sexton’s life and works.

Caroline King Barnard Hall, Sylvia Plath (New York: Twayne, 1998).

An introduction to Plath’s life and works.

Jack Elliot Myers, David Wojahn, and Ed Folsom, eds., A Profile of Twentieth-Century American Poetry (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1991).

Critical essays on the aesthetic and cultural influences on American poetry, including Mark Doty’s “The ‘Forbidden Planet’ of Character: The Revolutions of the 1950s,” much of which examines the role of Lowell and the Confessionalists in that decade.

Kate Sontag and David Graham, eds., After Confession: Poetry as Autobiography (St. Paul, Minn.: Graywolf Press, 2001).

Poets Billy Collins, Louise Glück, and others discuss the poetry of the self.

Harry Thomas, Berryman’s Understanding: Reflections on the Poetry of John Berryman (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988).

Critical essays, reviews, interviews, and memoirs regarding Berryman and his work.

Alan Williamson, Pity the Monsters: The Political Vision of Robert Lowell (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1974).

A study of Lowell’s poetry in light of his discontent with American society.

David Yezzi, “Confessional Poetry & the Artifice of Honesty,” New Criterion, 16.10 (June 1998): 14.

A retrospective review of the confessional movement prompted by the publication of Birthday Letters (1998), a collection of poems by Plath’s husband, the British poet Ted Hughes.

Categories: Literature

Analysis of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance

Analysis of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance  Analysis of Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Última

Analysis of Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Última  Analysis of Gertrude Atherton’s Black Oxen

Analysis of Gertrude Atherton’s Black Oxen  Analysis of Richard Wright’s Black Boy

Analysis of Richard Wright’s Black Boy

You must be logged in to post a comment.